How Combat Forged an Israeli Fighter Pilot

One month after graduating from the Israeli Air Force Academy, the Six-Day Arab-Israeli war broke out, thrusting Zvi Kanor into his first days of jet combat.

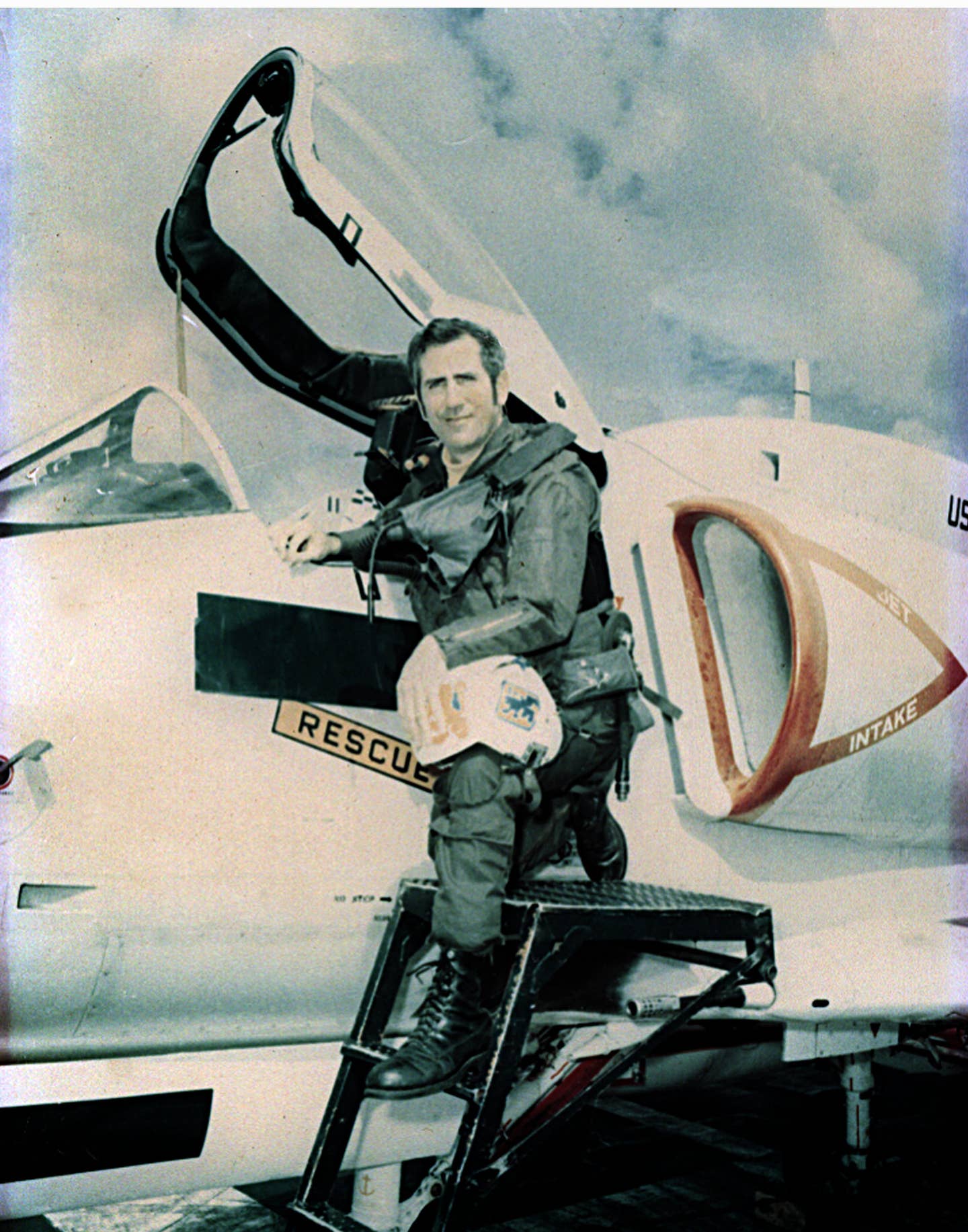

Zvi Kanor climbed the ranks from fresh recruit, pressed into battle, to Brigadier General in the IAF. [Courtesy: Zvi Kanor]

Editor’s Note: In the summer of 1967, 20-year-old Zvi Kanor earned his wings when he graduated from the Israeli Air Force Academy. One month after graduating, however, the Six-Day Arab-Israeli War broke out, thrusting him into his first days of combat. It would prove to be the opening salvo for a 27-year-long aviation career in the IAF for now-retired Brig. Gen. Kanor, who would go on to serve as a Wing Commander at Tel Nof Airbase. He retired from service in 1993.

Kanor recently sat down to discuss his early days as a fighter pilot, and the importance of transparency and accountability throughout ranks of the pilot community. Here are excerpts from that conversation, lightly edited for space and clarity, as told to FLYING.

I have to go back to the ’67 War, which was the Six Day War. I was a young pilot who graduated from the Air Force Academy about a month and a half before this war erupted. I was only 20 years old, and my experience was with the Fouga [CM.170] Magister, which was a [French two-seat] training airplane. It wasn't a combat aircraft.

The whole country was on alert for three weeks before the war started.

We moved from the training school, we moved to a Dassalt Ouragan, which was a[nother] French airplane. The first one that looked like a fighter aircraft. But because we were not experienced enough to fly this aircraft, the Israeli Air Force decided to open a new squadron for reserve pilots flying the Fouga Magister.

You should keep in mind that Fouga Magister had only a very small gun—7.62 mm—which is nothing. It cannot do anything to any tank. And the only real ammunition [we had at the time] were 75 mm rockets.

We graduated the fighter pilot [course] with only nine [in the reserve squadron]. At the time, nobody knew what's going to happen. We had three weeks to be trained on the aircraft, which was for training, but we used it as a fighter.

So we had about three weeks to really train for a different war, for stationary targets. What we could do is use the rockets against the tanks… and the radar. Against other targets, we didn't have the appropriate ammunition.

The war started at 8 o'clock in the morning. I was in a formation and each formation consisted of four aircraft. Nobody could speak over the radio because we kept silent, without anybody hearing what's going on.

During the first flight on the way to the targets [in Egypt], we lost the leader of the formation because we flew at a very low level above the ground forces that had AAA [anti-aircraft artillery]. They hit him and he fell down. We continued… and we completed our mission.

During the rest of the war, we flew in Egypt and in Jordan. You should keep in mind that we were at the time 20 years old. At this age, you're afraid. But, you're not married. You have just started your life, and you are very devoted to whatever you have to do.

Because this [aircraft] setup didn't have any way to enhance the way to [fire] on the target, you had to do whatever you did from a very close range.

For instance, in order to attack a tank, we used to shoot from… a very, very low level. Very close to the tank. You could see the people from the tank jump out because you were so close.

We flew at 100 feet, which is about 30 meters, in order to launch the ammunition. This was the first time that we flew like that—in war—because during the training you never fly at such a low level. The minimum level is 100 feet or 300 feet, but during the war, you had to fly and to get down to 30 meters. Even 20 meters.

During this war, by the way, my squadron lost six aircraft. You couldn't eject from the aircraft because there were no ejection seats. You just couldn't eject from the aircraft. So if you've been hurt, you couldn't get out of it. We had about 22 pilots in the squadron and we lost six of them during this war.

It was not an appropriate aircraft to fight with, but we had to fight against three different countries—in Egypt, Jordan, and Syria.

This was my first experience as a pilot, which happened all of a sudden before we were ready to do something like that. It was a tough war because the Israeli Air Force lost a lot of aircraft and pilots during this war, even though the victory was a huge one.

I was prepared for the next one.

There is something that is very important for me to tell you. I do believe that the big difference or the big advantage of the Israeli Air Force is the ability to debrief. What does it mean, debriefing? Debriefing means that when you are going to any sortie—any mission—that you are going to bring everything on the table.

One of the things that I think influenced the Israeli Air Force to be what it is, is the fact that from the very beginning, we used an 8 mm camera. Whenever you launched a rocket or bomb, it took the picture of whatever your eyes saw.

Then you come back to the ground. For the 8mm camera, you had to go to develop it and it took time. But our air force decided that we don't believe anyone, we just believed what the camera sees. What the camera sees, no one could manipulate. Nobody could tell stories.

Before the camera, we realized that pilots make a lot of mistakes.

During the years when video took place, all our airplanes used video cameras. …You hear everyone at the same time. You see each one of the cameras at the same time. You see and hear everything that was happening during the air combat.

Put Everything on the Table

I graduated from the U.S. Air Force's Air War College in Montgomery, Alabama. I respect very much the U.S. Air Force. It's very good. But there is one difference, which makes the Israeli Air Force a little bit different. I was the base commander of the biggest base in Israel, Tel Nof. I was, at the time, Brigadier General. In the Israeli Air Force, you used to fly every morning in a different squadron than the position in your base. In my time, there were six squadrons. I used to fly every day in a different one.

When I would come to fly, I was positioned within a formation of a two-against-two. My leader could be a lieutenant. The base commander, which is a brigadier general, led by a lieutenant, and this lieutenant is impacted by whatever the base commander recommends or says about him.

You fly with him and, because he's the leader, you know, if you do something wrong, he could say, "Did you see everything on the video?" Everybody sees everything. The leader can say, "Okay, you made a mistake here. You went under the minimum altitude, so you pay $100." In Israel, it's the shekel, but you have to pay. His future depends on the base commander, but nobody took into consideration the fact that he is a lieutenant. As long as he is the leader, he decides.

No matter whether you are in a civilian company or in the service or wherever you are, in order to change things that are wrong, you have to put everything on the table and to say, "Look, even though I am the general, I made a mistake."

This is the only way that you can change and become better than it was two days ago.

Subscribe to Our Newsletter

Get the latest FLYING stories delivered directly to your inbox