Over, Under, Sideways, Down: The Art and Science of Aerobatic Flight

Flying a clean aerobatic competition with no outs and no zeros can be just as satisfying as winning.

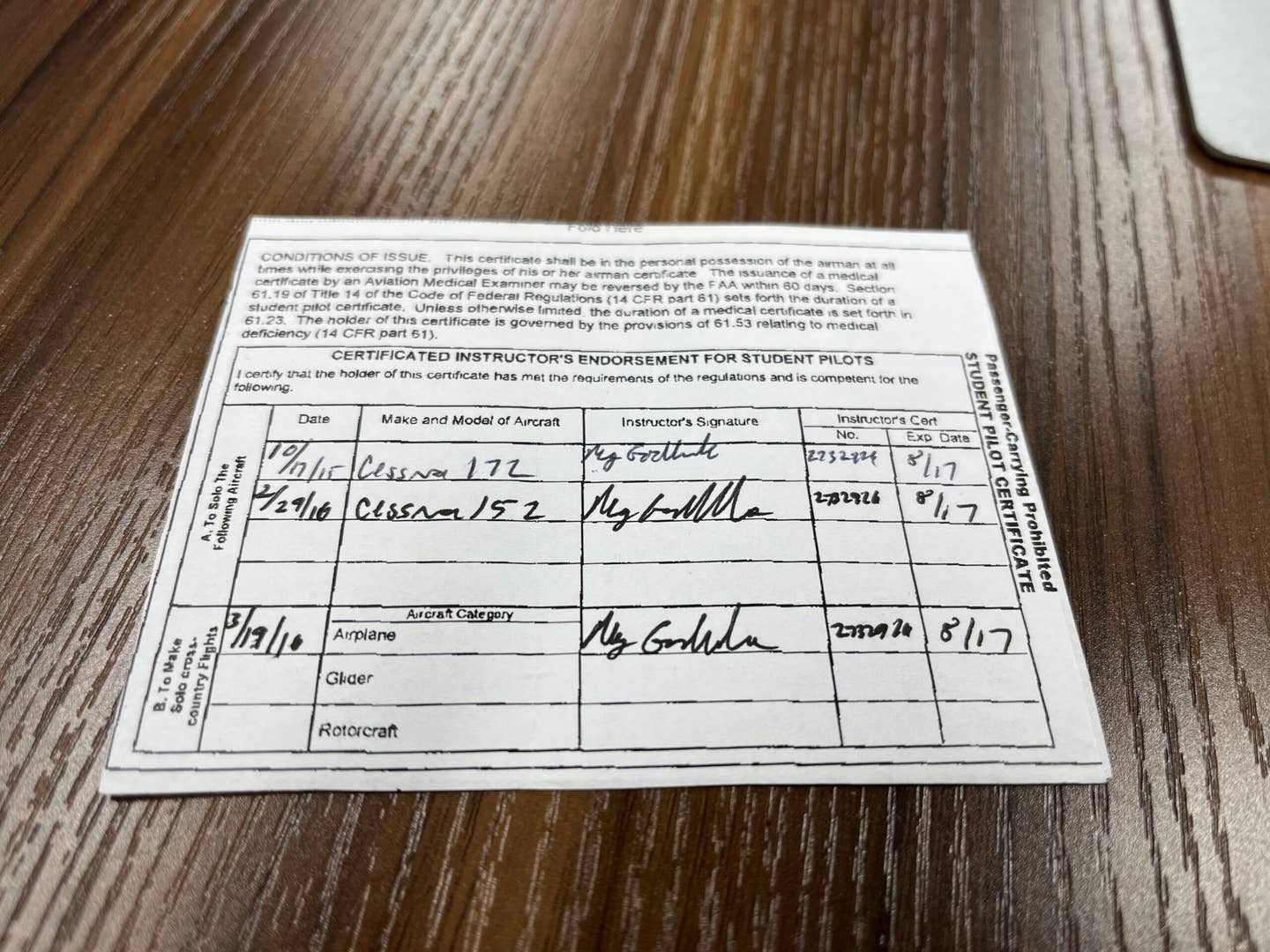

Aerobatic competitions in the U.S. include five classes, with increasingly difficult maneuvers and sequences. [Courtesy: Tyson Rininger]

How on earth did I get here? This is a question I have pondered many times while flying. Sometimes it’s because nothing is going my way. But on this day in 2011, at the FAI (Fédération Aéronautique Internationale) World Aerobatic Championship in Foligno, Italy, everything was just right.

I was doing circles at 4,000 feet agl in my Extra 300S, waiting nervously for the chief judge to radio me. Soon I would do flips and turns inside an invisible box in the skies in an attempt to impress the judges. As a kid I would spin airplanes around with a remote control. Now I was inside the airplane. The silence ended and I heard the chief judge’s thick British accent: “Contestant 34, the box is yours.”

I dove in and all doubts disappeared. The flight went really well, and after I landed, my teammates—who were standing on the edge of the taxiway—gave me a thumbs up. Best of all, our marvelous team coach, former two-time world champion Sergey Rakhmanin, ran towards me smiling. “This is the best I have ever seen you fly!'' he said. I was thrilled. But his next sentence brought me back to reality. “What have you been waiting for?” We both laughed.

My introduction to aerobatics came in 1978 while working at a local hobby shop. A regular customer, Don Chapton, asked if I would like to go for a ride in a Super Decathlon. Full of excitement, I met Don the next day at Sunrise Aviation at John Wayne/Orange CountyAirport (KSNA) in Santa Ana, California. We looped, rolled, and spun over the Pacific Ocean. This was my first introduction to G force—the force pushing the pilot into the seat during positive G maneuvers and out of the seat during negative Gs. If you don’t have a friend who can introduce you to aerobatic flying, the International Aerobatic Club is a wonderful resource. This organization has regional chapters and sanctions aerobatic contests throughout the country. Joining a chapter is an easy way to get involved.

Aerobatic competitions in the U.S. include five classes: Primary, Sportsman, Intermediate, Advanced, and Unlimited, with increasingly difficult maneuvers and sequences. The floor of the box sits at 1,500 feet agl for the Primary and Sportsman classes and drops progressively. In the Unlimited class, the floor is only 328 feet agl. To help the pilot keep track of the sequence, the maneuvers are drawn using a symbolic language developed in the 1930s by Jose Aresti of Spain. Aresti created a symbol for each aerobatic maneuver, categorized them, and assigned them a numeric level of difficulty called a K-factor. It’s an aerobatic shorthand used in a similar way that musicians use sheet music. Each maneuver is graded from zero to 10 multiplied by the K-factor. A forgotten or unrecognizable maneuver receives a zero. In a typical contest, three flights are flown. The first round is called the “Known”—a predetermined sequence flown by everyone in the class. The second round is the “Free.” This sequence is built by each pilot but there are very specific requirements for how it can be constructed. The third round is the “Unknown,” which is only flown in the Intermediate, Advanced, and Unlimited classes.

Flying a clean contest with no outs and no zeros can be just as satisfying as winning. The surfing community has coined the phrase “Soul Surfer”—for one who surfs for the sheer pleasure of surfing. This has its place in aerobatics too. That pilot's a “Soul Flyer."

Subscribe to Our Newsletter

Get the latest FLYING stories delivered directly to your inbox