Airplane Math: When Do Upgrades Make Economic Sense?

The calculus often comes down to avoiding becoming upside down, but not at the expense of enjoying your perfect airplane.

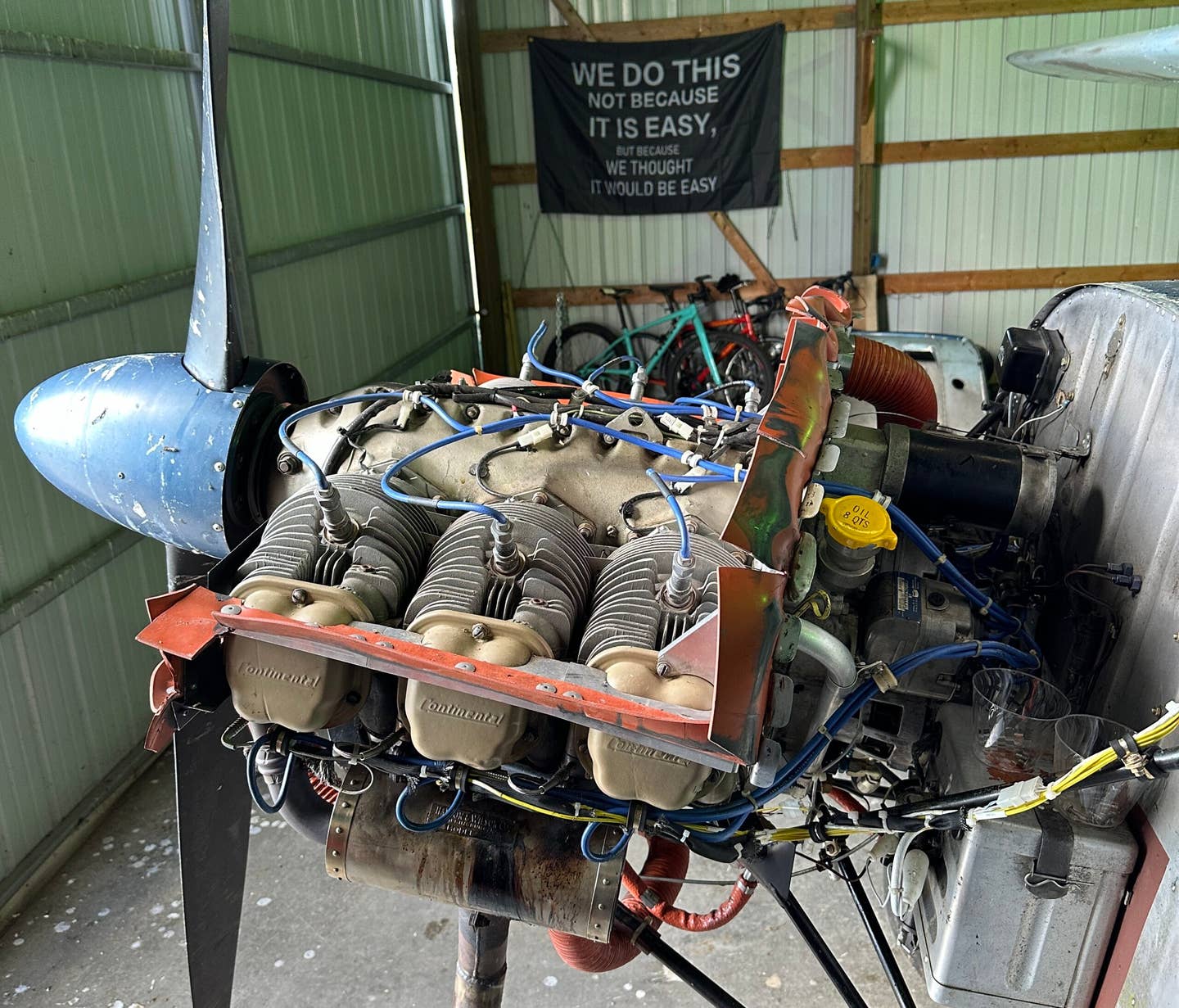

Most owners never recoup their investment in major upgrades such as a new instrument panel or a more powerful engine. But it’s important to consider the long-term benefits that might not show up on a spreadsheet. [Credit: Jason McDowell]

Readers contact me pretty regularly for advice regarding airplane shopping, purchasing, and maintenance. I can only assume they’re inspired by the notion that an individual lacking flying skills, business acumen, and finances can successfully navigate aircraft ownership. I’ll admit I myself am often amused that I’ve made it this far.

It’s enjoyable to help, though. Whether it’s a new pilot exploring ownership for the first time or a seasoned expert weighing upgrade options, I find it rewarding to help others avoid some of the hard lessons with which I’ve had to contend thus far on my own journey.

I recently spoke at length with two individuals asking for ownership advice. One was considering a panel upgrade, weighing the pros and cons of a few options that ranged from some minor modifications to a complete overhaul. The other was torn between upgrading the engine and propeller on his Cessna 170 versus selling it and buying a larger Cessna 180.

In each case, the most attractive option was to invest a fairly substantial amount of money into the existing airplane. Panel guy knew he wanted full IFR capability, and he knew he liked Garmin’s latest avionics. And 170 guy loved almost everything about his airplane except for the modest power. Each recognized that a big upgrade would result in their perfect airplane…but each shared the same reservation—losing money on the airplane upgrade and reasoning they’ll never get it back through resale.

They’re not wrong. In most cases involving major upgrades, the money spent on parts and labor will exceed the additional amount you can command when reselling the airplane. The majority of the upgrade cost becomes sunk, and this was the hangup I kept hearing.

In the case of the full panel overhaul, the entire panel plus labor was forecast at around $60,000—nearly the value of the airplane itself. The resale value of the unmodified plane was around $80,000. Based on what I’ve seen in the classified listings, this would rise to perhaps $100,000 to $110,000 with the new panel installed. So about half of the panel cost would be money spent and never seen again.

It was the same story with the Cessna 170 owner looking for more power. Yes, he could upgrade the engine and propeller, but he’d never get that money back out of the airplane when the time came to sell it. This is why he was considering selling the 170 and upgrading to the 180. He loved his 170, but the spreadsheet said the 180 would be the wiser investment.

I asked both owners a few key questions, including how long each expected to own their airplane and what they enjoyed most about it. Their replies were predictable. They loved their airplanes and expected to continue flying them for another 20 years or so. Each had already spent significant time and effort to get them sorted and set up to their liking, and in each case, the upgrade they were considering would eliminate their least favorite aspect of the airplane.

It ultimately came down to the question of whether each upgrade must earn its place and someday recoup its entire cost. I advised the owners to pay attention to this factor but not live by it. In other words, try to avoid becoming upside down on each upgrade, but not at the expense of years of enjoying your perfect airplane.

In the case of the panel upgrade, I offered a scenario. Suppose the complete new panel ultimately “loses” half its value when the airplane sells. Over the course of 20 years, this amounts to little more than a cell phone bill every month. And chances are the appreciating value of the airplane itself will absorb that amount and then some.

The flip side is to live with an airplane that’s almost perfect but annoys you in the same persistent manner throughout every flight. For panel guy, this would mean living with a panel that’s VFR-only or IFR-capable but imperfect. Personally, I’d almost rather have the option that’s far from perfect because I find almost perfect to be maddening.

For engine upgrade guy, this would mean one of two things. He could live with the relatively anemic thrust, takeoff, and climb ability of the stock 170. Alternatively, he could sell it and upgrade to the 180—but that would introduce higher fuel burn, higher insurance rates, and years of finding, buying, and sorting an airplane to get him back into the groove of stable, predictable ownership. For him, putting the finishing touches on an almost perfect airplane seemed to make the most sense.

Ultimately, I provided both owners with the same advice. Look at the cost of a major upgrade over the entire length of time you expect to own the airplane and take the appreciating value of the airplane itself into account. Twenty years from now, it’s unlikely any of us will look back and lament missing out on an additional $125 per month on an individual upgrade. But it’s entirely likely we’ll look back on a couple of decades of flying adventures made that much safer and more epic by taking place in the perfect airplane.

Subscribe to Our Newsletter

Get the latest FLYING stories delivered directly to your inbox