Pride of Ownership and the Insult of Neglect

If we can collectively intervene and convince the neglectful owners to pass their machines on to people committed to maintaining them, we all benefit.

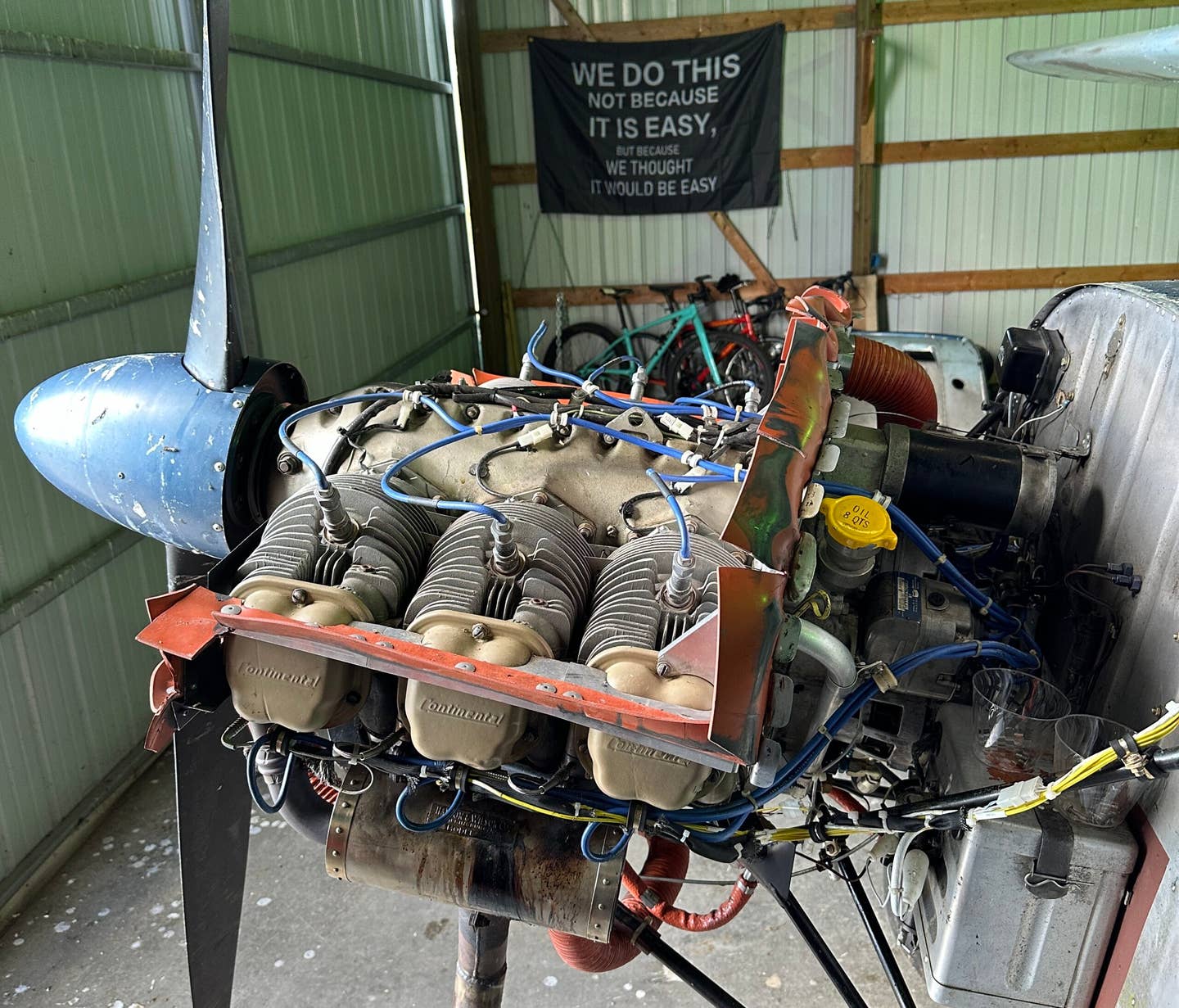

Once a beautiful airplane, this 1952 Cessna 170B has been neglected for decades, likely to the point of no return. [Credit: Jason McDowell]

The year was 2004, and what began as an enjoyable stroll across a quiet ramp at a small rural airport had become somewhat heated. My friend Matt and I stopped by on a whim to check the place out. Neither of us was an airplane owner at the time, and we enjoyed daydreaming as we learned about all the various types of general aviation aircraft in the hopes of owning one someday.

We were met with example after example of depressing neglect. Over here, a Tri-Pacer with ratty fabric and visible rust on cylinders. Over there, a Luscombe with flat, cracked tires and yellowed windows. Next to the Luscombe, a Cherokee 140 covered in bird droppings and ravaged by harsh Michigan winters.

From the perspective of two private pilots without the means to purchase their own airplanes, it was inconceivable that an owner could simply let their machine rot in such a manner. In our minds’ eyes, we envisioned airplane ownership to involve substantial amounts of time cleaning, polishing, and doting. Pride of ownership mattered, and we felt insulted by the utter neglect standing before us on flat tires. These owners had evidently tossed their once-airworthy machines aside, letting them deteriorate without a care. And it made us angry.

It was shameful, and as we continued our walk, we devised a plan.

One day, when we both had enough money to purchase politicians and enact legislation to our liking, we’d form our own company. This company would be modeled after Child Protective Services. It would work hand-in-hand with the authorities to identify and confiscate aircraft that have been neglected by their owners.

More importantly, the company would work with local pilot groups to identify loving homes to which each aircraft could be donated. A robust screening process would ensure the new owners would fit into a specific financial segment—sufficient funds on hand to fly and maintain a small airplane but not enough to purchase one. Through these efforts, airplanes would be saved from ruin, the dreams of countless private pilots would be fulfilled, and GA would be revitalized.

Sadly, the company never came to fruition. While I could now possibly afford to purchase a local village alderperson, meaningful change through crooked legislation remains out of financial reach. But the dream is still alive in the form of rehoming efforts that I continue to this day, as I take special note of derelict aircraft and keep an eye out for private pilots who could potentially save them from total deterioration.

My most recent mission came, as most do, by word of mouth. While chatting with my friend Dan about interesting places to fly, I mentioned in passing how I’d like to go visit a private grass strip where I spotted a Cessna 170 that has apparently been put out to pasture. I’ve got a friend in Michigan who is after a 170 and happens to possess sufficient mechanical ability to perform a light restoration, and she would be a great candidate to save the airplane.

Dan perked up. He knew of a similar 170 not too far away, and he was looking for an excuse to fly his 182. A few days later, we were on our way to check it out. But upon arrival, we discovered it was in pretty bad shape.

It was a shame. The original 1950s-era paint was beautifully weathered to a rat rod-like patina. The panel, although dirty and in need of updating, was in shockingly nice shape. And it happened to be a desirable B model. But the exterior had been exposed to decades of Wisconsin winters, and both rust and corrosion were apparent throughout the airframe.

The airplane rescue mission was, therefore, a bust. Most of them are. But as I visit new airports and encounter unused aircraft, I continue to play matchmaker for friends and acquaintances, attempting to connect the poor airplanes with wishful aircraft owners. This, I think, is something we all should be doing.

While total restorations are beyond the capability of most first-time owners, light restoration work can be a simple matter of paying a bill. Presented with the opportunity to obtain an old Cessna or Piper for well below market price and then spend several thousand dollars to get it up to speed, a prospective owner just might discover the math checks out.

The key is to catch these ignored airplanes before they’ve deteriorated beyond the point of no return. If we can collectively intervene and convince the neglectful owners to pass on their machines to people committed to maintaining them, we all benefit. The affordable aircraft population will experience less of a decline, prices will become more stable, and as more people do more flying, GA will become healthier and more popular.

Those of us who own our own aircraft should occasionally be reminded to avoid letting our beloved machines sit idle and deteriorate beyond intervention. If medical issues, financial challenges, or life in general begins to result in cobwebs on our airplanes, we need to proactively get creative and find ways to keep them flying and healthy. Maybe we invite trusted friends to fly them once a month for us. Maybe in exchange for an annual inspection, we allow our A&P to fly the airplane a certain amount of hours per month.

Alternatively, we could sell one or more fractions of it and begin a partnership. This would result in instant cash flow. It would keep the airplane flying, and it would build up a nice emergency maintenance reserve, ensuring it is well cared for. These days, there’s no shortage of wishful pilots who would love to become an owner in such a manner.

With any luck, efforts like this will slow the decline and deterioration of affordable aircraft. Best of all, Matt and I will no longer have to form Airplane Protective Services to confiscate and save them. After all, we’d rather be flying.

Subscribe to Our Newsletter

Get the latest FLYING stories delivered directly to your inbox