NASA Astronauts Detail Daily Life, Firsts Aboard International Space Station

Frank Rubio, Stephen Bowen, Woody Hoburg, and Sultan AlNeyadi participate in a panel discussion for the media at NASA Headquarters in Washington, D.C.

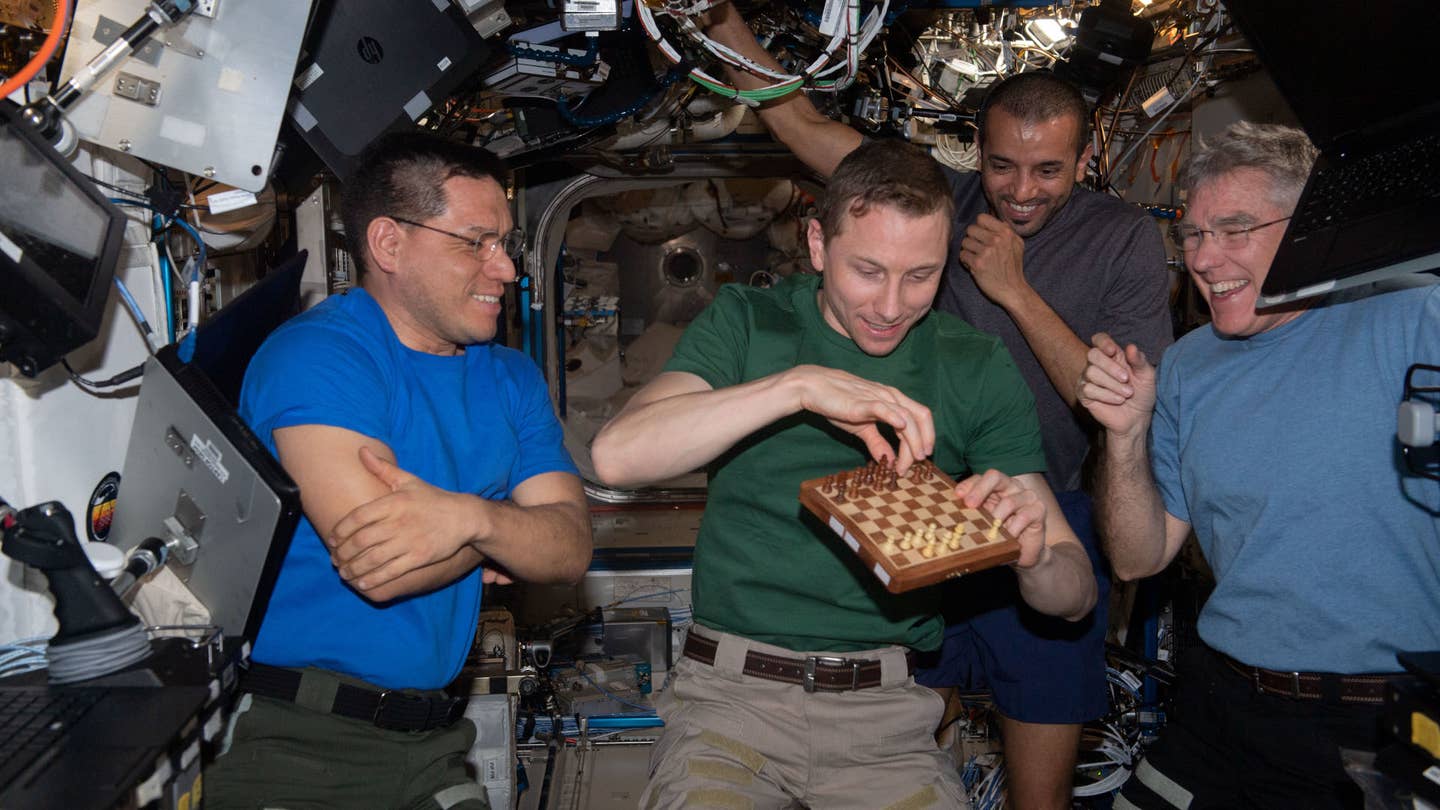

Astronauts Frank Rubio (from left), Woody Hoburg, Sultan AlNeyadi, and Stephen Bowen play chess with NASA mission controllers. [Courtesy: NASA]

WASHINGTON, D.C. — Four people, six months, and hundreds of experiments that could alter humanity’s future.

NASA’s SpaceX Crew-6 mission, which concluded in September, sent NASA astronauts Stephen Bowen and Woody Hoburg and United Arab Emirates astronaut Sultan AlNeyadi on a 186-day trip to the International Space Station, where they rendezvoused with NASA astronaut Frank Rubio. But it was anything but a vacation.

“I used to joke about the fact that a lot of times in our videos, when we show what's going on, we spend about a third of our time showing the fun stuff,” Bowen told FLYING at a media event at NASA Headquarters alongside his three crewmembers. “Work is way more than a third of the time we spend up there.”

The mission included several firsts. Rubio, for example, set the U.S. record for most consecutive days in space by the end of his 355-day stay, which was extended six months after the capsule that brought him to the space station was damaged. AlNeyadi became the first Arab to complete a spacewalk.

But the astronauts also conducted more than 200 experiments during their stay at the orbital lab—many of which could address pressing needs on Earth and far, far beyond.

To the Space Station and Back

Crew-6 began with the launch of a SpaceX Dragon Endeavor capsule, strapped to a Falcon 9 rocket, from Kennedy Space Center in Florida. Bowen, Hoburg, AlNeyadi, and Russian cosmonaut Andrey Fedyaev were its occupants. Rubio had launched previously aboard a Soyuz MS-22.

Bowen, a veteran of multiple trips to the space station, was right at home. But for Rubio, Hoburg, and AlNeyadi, Crew-6 was their first time in space.

“Learning to fly for the first couple days is pretty difficult,” Rubio said.

For AlNeyadi, adjusting to the lack of spatial awareness was the biggest challenge

“Everything is very quick aboard the space station…We have 16 sunrises and 16 sunsets every day,” AlNeyadi told FLYING.

Bowen said the orbital lab has come a long way since his first visit in 2008. He was part of several assembly missions, which doubled the space station’s occupancy from three to six, installed technology such as a water recycling system, and delivered research and stowage modules. Crews also replaced the laboratory’s batteries several times.

“We were part of that first step of really making the space station functional,” Bowen told FLYING. “We did a lot of things with just three people on board. But as soon as we got up to six people, the ability to do the actual science—the business of the space station—exploded.”

The astronauts spent the next six months growing plants, researching tissue chips for heart, brain, and cartilage tissue, and conducting hundreds of other experiments for ISS Expedition 69. NASA expeditions refer to the crew occupying the space station—Rubio, Bowen, Hoburg, and AlNeyadi were the 69th such team.

After finishing their work, the astronauts began reentry, splashing down on September 4 after 186 days.

“Becoming a plasma meteorite when you’re coming home is pretty exciting stuff,” said Rubio.

But the research and experiments the crew performed are expected to have an impact long after the mission’s conclusion.

Charting the Future

Despite Rubio’s excitement, launch and reentry may have been the dullest segment of the mission—the crew had more than 200 experiments to fill their time.

“The work is continuous; the work is ongoing,” said Bowen. “Maintaining the space station, like you maintain your house, takes a big chunk of your time. The amount of science we can do now is incredible. Every day we were up there, there's four of us in the [U.S. Orbital Segment] working.”

Just days after the astronauts’ arrival, they received a cargo vehicle full of materials for experiments. Crewmembers worked throughout the day, sometimes together and sometimes individually, coming together at dinnertime to debrief.

“We are testing hundreds of technologies, and many of them are becoming spinoffs for humanity when utilized here on Earth,” AlNeyadi told FLYING.

For example, astronauts studied how they could grow plants such as tomatoes in harsh and unforgiving environments, either on Earth or in space. They also applied experimental medications to heart cells and printed biological material such as knee cartilage, using technology that could one day print organs for patients on the blue planet.

The crew even ran competitions with university students. Competing teams were able to program a flying robot and control its flight on the space station from Earth.

Perhaps the most consequential research involved a water recycling system, which allowed the astronauts to drink their own urine for the majority of their stay (move over, Bear Grylls). The system may sound outlandish, but it could hold real benefits for humanity.

“Imagine taking the same technology and providing it to people in need in remote areas where they lack water,” said AlNeyadi.

The experiments will also play a key role in NASA’s Artemis program: a series of missions intended to return Americans to the moon for the first time in half a century. According to the crew, learning to live and work in space will be essential for those journeys. Artemis II will send astronauts into lunar orbit in 2025, while Artemis III will attempt to land them on the moon’s surface the following year.

“Knowing that you’re affecting the future of humanity and inspiring future generations, that’s super important to us,” said Rubio.

As important as their work was, the astronauts would not have been able to complete it without finding ways to blow off a little steam.

One method was to simply go outside. Each crew member got the opportunity to complete a spacewalk, including AlNeyadi, who became the first Arab to accomplish the feat.

“Getting in the suit, going outside, and doing important repairs on the station while seeing those views of Earth was just very special,” said Hoburg.

The crew had to get creative at times—Bowen baked pies for Pi Day, and Rubio cut the other astronauts’ hair. But they found plenty of ways to exercise and have fun—and by the end of the mission, they had become a family.

“What a great group of people I had to hang out with for six months,” said Bowen. “It was just incredible.”

A Collective Effort

Crew-6 included the first astronaut of Salvadoran heritage to reach space (Rubio) and the first Arab to complete an extravehicular activity (AlNeyadi). Those feats are symptoms of a broader trend: the globalization of space exploration.

At one point during Expedition 69, there were 11 astronauts aboard the orbital laboratory, which is designed for a maximum of seven. Occupants hailed from the U.S., UAE, Russia, Denmark, and Japan.

“It’s a very intense period when you’re handing over to a new crew, because you’re basically teaching them a whole new lifestyle in a few weeks,” said Rubio.

But the transition was also a welcome development, according to Bowen.

“We actually get a chance to meet a lot of our colleagues around the world before we ever fly,” he said. “So having that crew come on board, I knew every one of them. It was a lot of fun. It's just great to have new people on board—and it's another sign you're going home too.”

AlNeyadi said the UAE already has benefited greatly from its activities in the final frontier. The country’s space agency has only been around for two decades. But in that short time, it has sent a satellite, Martian probe, and the nation’s first astronaut, Hazza Al Mansouri, into space.

“That was an eye opener for everybody. After that, everybody—every young student in the school—wanted to be an astronaut,” said AlNeyadi, who was appointed UAE minister of youth this month.

The Emirati’s own trip has had an impact too. For example, he said it helped catalyze the UAE’s participation in NASA’s Lunar Gateway project, which aims to build a space station orbiting the moon. The country is the fifth to join the partnership.

NASA is also increasingly relying on private industry to help fill certain gaps for Artemis, a contrast to the government-heavy Apollo program. Rubio said he helped certify all SpaceX launch and recovery assets before his mission, a reflection of the agency’s tight relationship with it, Blue Origin, and other commercial partners.

The hope is that greater collaboration can kick off a groundbreaking new era for space travel, one in which humans are continuously occupying the final frontier.

Bowen shared a story about a pair of glasses he found floating aboard the space station, which he mistook for his own. They weren’t Rubio’s or Hoburg’s either, and AlNeyadi didn’t wear glasses. As the crew soon realized, they belonged to an astronaut who had stayed at the orbital lab years ago: a relic of humanity’s persistent effort to uncover the mysteries of space.

Crew-7 astronauts—picking up where Crew-6 left off—splashed down earlier this month, a few days after the Crew-8 team arrived. Perhaps they too will discover the remnants of explorations past. Undoubtedly, they will build on the foundations of previous missions and push humanity forward.

Like this story? We think you'll also like the Future of FLYING newsletter sent every Thursday afternoon. Sign up now.

Subscribe to Our Newsletter

Get the latest FLYING stories delivered directly to your inbox